How (Not) To Monetize A Movie

The twelve-year journey to make, release and rerelease my debut feature illustrates the untenable current state of indie filmmaking and distribution

Introduction

My first feature, Good Funk, is the story of three generations of Afro-Caribbean immigrants living in Brooklyn whose lives intersect through acts of kindness. The movie was the product of a first-of-its-kind film training and visual literacy program where young Brooklynites learned filmmaking craft, shared their stories and collaborated for pay on a feature film production. The result is a portrait of love enduring and a testament to finding family in unexpected places.

The entire project cost around $55k to produce. I shot it with a small crew of friends in 2014. We took our time with the editing process and ended up having a modest world premiere at the Sidewalk Film Festival in 2016. We had a short but respectable fest run that did not yield any viable distribution offers.

Due to both my lack of preparation and the rapidly deteriorating conditions of the indie film marketplace, Good Funk spent the next few years sitting on a shelf: not making money, not available anywhere and hardly seen by anyone.

Distribution

In August of 2020, my partner recommended I reconnect with distributors who had initially passed on the film. She speculated that, in the wake of the BLM protests, they might have more interest in movies like Good Funk that feature predominantly black casts and center the experiences of black Americans.

I reached out to several distributors, two of whom were now interested to release the movie. Neither offered a minimum guarantee — an advance upfront — but both were willing to invest time, resources and a small marketing budget.

I ended up signing a global all-rights deal with 1091 Pictures (formerly the film and television subsidiary of the Orchard). They had released several well-known independent pictures and seemed to prioritize transparency. They had a tech platform, Streamwise, which allowed filmmakers to view comprehensive royalty reports in real-time. They were flexible in contract negotiations and accepted everything my lawyer and I requested. Most importantly, they were interested in the “making of” aspect of Good Funk — the apprenticeship program — and saw it as a foundational part of the marketing campaign.

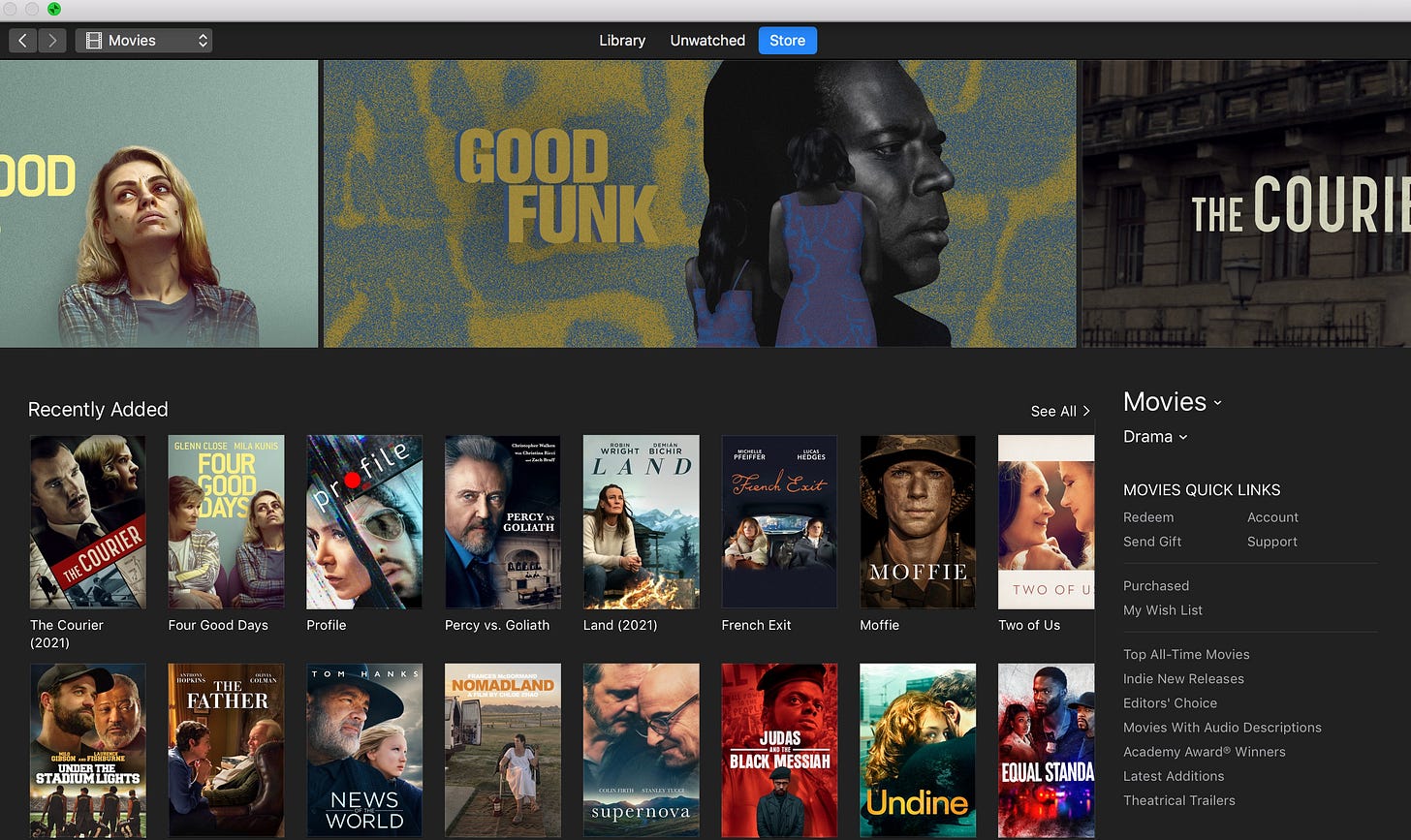

It was a successful partnership at first. The 1091 team delivered on their initial promises. They created cool key art and a compelling trailer for the film (which was released exclusively on comingsoon.net). They arranged an interview with PopMatters during which I was able to discuss the apprenticeship program at length. They got us featured in USA Today’s List of Summer Movies. On the day of our digital release — June 8, 2021 — we had a banner in the iTunes store.

Royalties

The film made a couple hundred dollars from purchases and rentals in its first month on transactional video-on-demand (TVOD) platforms. Cool marketing assets had been created, but there was neither a strategy nor the support to build buzz with them. When the film did not immediately catch fire, 1091 shifted their focus to other projects. In the following months, as the movie became widely available on subscription (SVOD) and then ad-based (AVOD) platforms, revenue dropped precipitously until we were making virtually nothing.

One reason for this is logical and natural: as a film gets further into its release cycle, and starts appearing on SVOD and AVOD platforms, the per-view royalties shrink. At the same time, I did not realize how small the royalties are until I saw them for myself.

Because I had access to real-time reports on Streamwise, I was able to see how many minutes my film was viewed and how much revenue was generated by those minutes.

In the first quarter of our streaming release, Good Funk was watched for over 13500 minutes on Amazon Prime. The film is 73 minutes long. 13500 minutes is roughly equivalent to 185 people watching the film start-to-finish. For those views Amazon paid us 55¢ total. 1 cent for every 245.46 minutes viewed. By these metrics, to make $100, Good Funk would need to be fully watched about 33,624 times.

This is infuriating, honestly fucking insane, absolute highway robbery. If 33,000 attended a theatrical screening of the film, at $15 per ticket, and production kept 25% of the gross revenue, our net would be $123,750. If 185 people bought Good Funk for $1, and we kept 100% of the proceeds, we would net $185, which is about 336 times more than 55¢. It is a terrible joke.

At some point, Streamwise went offline. I emailed my contact at 1091. “We have stopped using Streamwise and launched a new dashboard,” they informed me. “You should have been notified a few months ago.”

I was then sent an invite to get enrolled on the new platform (Looker). Once I was set up, I began reviewing the reports. Our total revenue on Looker was approximately 17% less than it had been on Streamwise. I inquired about the missing revenue.

“I do not believe Looker has historical statements,” they replied. “This should only be the revenue since the first accounting report into Looker.”

“Can we reach out to accounting and get a hold of those historical statements pre-Looker?” I asked. “Or at the very least, can you find and send along the cumulative revenue of the film?”

“Uploading historical data is a part of our phase 2 process of our roll out. I will check in with finance to provide the cumulative revenue.”

I did not hear from them for the next ten months and never received the information I requested. I eventually followed up.

“I was over on the Looker page recently, and noticed that it still hasn't been updated with historical data from the first four months surrounding Good Funk's release. Any idea what's up with that?”

“Unfortunately the company did not move forward with backfilling historical data into Looker. As you can imagine we have thousands of films so getting everything reformatted and prepped for the new platform was quite a heavy lift for the accounting team. It’s just not something that’s possible at this time and we don’t have a timeline for when it could happen.”

“How am I supposed to know how much money my film has made in revenue from release until now?”

“We advised licensors to pull down revenue data prior to the shutdown of Streamwise. If you did not do this we can ask accounting to compile but it might take some time as they are short staffed and backed up.”

“Yes, I was never advised to do that, and so if that could be compiled at some point in the next month or so, it would be much appreciated.”

I never heard from them again.

Bankruptcy

Fast forward eight months, to December 2024. I am attending a discussion with Keri Putnam about her groundbreaking study of the American film landscape, co-hosted by

and . They are discussing how several distribution companies who popped up in the mid-2010s — at the height of the VC-backed streaming gold-rush — have since folded. Jon mentions a few recent examples, then says something like “1091 is about to shutter, if they haven’t already.”Um, what?

I quickly start googling and find several concerning articles:

Chicken Soup for the Soul Buys 1091 Pictures for $15.6M (March 2, 2022)

Filmmakers Take Legal Action Against Chicken Soup for the Soul Entertainment as It Faces ‘Cash Flow Issues’ (December 20, 2023)

Filmmakers Take Self-Help Publisher Chicken Soup For The Soul Entertainment To Court Over Back Pay (January 24, 2024)

Redbox owner Chicken Soup for the Soul files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection (July 2, 2024)

I reach out to my contact at 1091 and receive the following auto-response:

“As of June 14th, 2024 I am no longer with Screen Media / 1091 Pictures.”

I receive an additional auto-response from a person I do not know:

The company [1091/CSSE] has filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy protection, all employees have been terminated.

Sorry, but I have been given no information or instructions on moving forward, only that if you have a claim against the company:

"please file the claim with the US Bankruptcy Court for the District of DE. Google for instructions."

Legal Action

I reach out to my lawyer and explain the situation, and he connects me with a bankruptcy lawyer at his firm.

This lawyer informs me that the proceedings are taking place in Delaware, where CSSE is established, and that I will need to hire a Delaware-based bankruptcy lawyer to proceed. She connects me with a Delaware-based lawyer who is familiar with the case and has helped other filmmakers recover their films.

I meet with the Delaware-based lawyer. After learning details about the case, he is confident we will be able to recover the rights to my movie. The situation is made easier because I am not trying to claw back potential owed revenue (which could complicate things). I sign an agreement, pay a retainer and he gets to work.

Within a month, the lawyer had gotten a signed order from the Delaware Bankruptcy Court terminating my agreement with 1091/CSSE and returning all rights of Good Funk to me. The entire process cost around $2500. If you are in a similar situation, I recommend reaching out to Michael Busenkell.

I now had the rights back to my movie. What would I do next?

FilmHub

I wanted to experiment with what else is out there beyond the traditional distributors. I spoke with a few companies who are exploring and offering alternative models for releasing movies. I ended up going with FilmHub, a distribution marketplace that allows filmmakers to distribute to digital platforms and collects and pays out royalties on the filmmaker’s behalf. FilmHub takes 20% of revenue generated and the rest goes to the filmmaker. The filmmaker retains all rights to their film at all times.

Their process is straight-forward. You upload your film and accompanying assets and submit them for a quality check (QC). If you do not pass QC, they explain why and tell you how the issue(s) can be resolved. You have three chances to pass QC.

FilmHub can assist in making changes required to pass QC. On their website, they offer a comprehensive a la carte menu of supports and services. They will, for example, caption your film or create key art for it, and their prices are competitive.

Perhaps the biggest selling point is that they charge $0 upfront to upload and QC your film and assets. There are costs if you choose to (or need to) add something from the a la carte menu, but if not, the $0 basic plan is sufficient for one filmmaker distributing one film. The only drawback I have found is limited access to data and analytics: an upgraded plan is required to receive detailed performance insights for all available platforms. For a back-catalogue title like Good Funk, this information would be nice but is non-essential.

Once Good Funk passed QC, I personally issued DMCA Takedown Notices to all the platforms where the movie was currently streaming and/or available for rental and purchase. Some of the platforms responded immediately and pulled down the movie without fuss; others were a bit more difficult and required more harshly-worded emails. After about six weeks of hard work, the movie was not available anywhere.

At this point, FilmHub started availing (pitching) the title to potential partners. In the past few months, they’ve licensed the movie to seven platforms.

If you wanna try FilmHub for yourself, use this referral code.

You can rent/buy Good Funk here, or stream it here.

Lessons Learned

I did not know what I did not know about festivals, distributors, release windows, marketing, rights and more. Here are six things I wish I had been aware of and done differently.

I did not set a clear goal for the distribution of the film.

talks about how films need to prioritize their goals early on in the process and use their top priority to shape every aspect of their release. Every filmmaker wants their film to get press, make money, have a socio-cultural impact, be seen by lots of people and launch their career. When resources are limited, it is essential to decide which of these objectives is of utmost importance and which can be deprioritized. The prioritization of goals reflects both a film’s strengths and its weaknesses. I wanted everything with Good Funk and ended up achieving not much as a result. In hindsight, I should have picked one primary goal and developed a strategy to align with and work towards that particular goal.Once you set a goal, how do you determine if it has been met? When I was making and releasing Good Funk, this question never crossed my mind. I did not know how to measure success beyond obvious indicators like views and revenue. I realize now that metrics and key performance indicators (KPIs) are essential for raising funds and measuring success. Every film defines success differently — An Inconvenient Truth wants to educate, Conclave wants to win awards, The Minecraft Movie wants to make money. Metrics and KPIs that encapsulate a film’s top priority are crucial for analyzing strategy and its implementation.

I knew nothing about film rights, neither how to negotiate nor exploit them. My initial agreement with 1091 was a global all-rights deal. Without thinking twice, I gave away all the rights to my movie for $0 upfront, even rights that 1091 had no interest in exploiting. I should have negotiated a split-rights deal, licensed to 1091 only what they would exploit, and retained all the other rights so I could continue monetizing the film in other ways.

It was almost five years between our festival and streaming premieres. In this stretch — not counting festivals — we only did one theatrical screening and two grassroots screenings. I did not reach out to or partner with any community organizations. I did not think about who exactly my audience was: where they are, how they consume media, how to reach them. I expected somebody else to do this and nobody did and the film suffered as a result. I was foolishly oriented towards distributors when I should have been thinking about the audience and building digital and IRL communities around the film from day one.

We had no digital release strategy beyond the traditional waterfall of TVOD to SVOD and AVOD. In each stage, the goal was to be on as many platforms as possible, even though most of our transactions were on Amazon and most of our streams were on Tubi. In hindsight, we should have considered scrapping the under-performing platforms and consolidated our efforts around driving traffic exclusively to Amazon and Tubi.

Even when the digital distribution system is “working”, it is not working for independent artists. We need ways for fans to directly pay filmmakers for their work. Each indie film release moving forward should be treated as an opportunity to experiment with new direct-to-audience release strategies. To ensure a sustainable future for radical, cool and uncompromising movies, filmmakers must take control of the marketing and distribution of their work.

Feel free to rent, buy or stream Good Funk on the major platforms, but know the revenue your view generates will mostly go to rich guys who had nothing to do with the film. If you want to watch the movie and directly support the team, donate a few dollars via my Tip Jar or Venmo (@Adam-Kritzer), include your email address in the contribution (or DM me), and I’ll send along a private rental link for your viewing pleasure. If one person pays me $3 for Good Funk, I will make more than if 1000 people stream it on Amazon. Success is relative; I like my odds. <3

Thanks for reading AMAUTEUR, a production and distribution newslabel that makes, releases and writes about independent movies and music. If you dig what we’re putting out, please share our work with your friends, become a free subscriber and consider making a one-time donation via Tip Jar.

Great article, when you switched to the new distribution, how much did it bring in. We all want to hear it would fund the next production. So I am interested in the reality, thanks

I've been sitting on this article for awhile, waiting for time to read it carefully. Thanks for providing a clear case study.